We’ve talked in these pages about the famous Japanese dog Hachiko, who went to the train station every day to wait for his owner to come home from work — even for years after the owner died, until his own passing. The dog, who became a national symbol of loyalty in Japan, was found to have had four meat skewers in his stomach (think kabob sticks) at the time of his death. They didn’t kill him — cancer did — but they could have.

“A dog will actually swallow a kabob stick whole,” says Your Dog editor-in-chief John Berg, DVM. “It goes right down the esophagus and into the stomach. It can’t get out the other end of the stomach because the exit passageway is too narrow. These sticks, because of their length, have a tendency to get caught cross-wise in the stomach. Then one side pierces a hole in the stomach wall, and the stick wedges out through that hole and begins to migrate. It can go through the diaphragm and into the chest cavity or somewhere in the abdomen, which houses the liver, pancreas, kidneys, and other organs. We’ve even seen them lodged in the lungs.

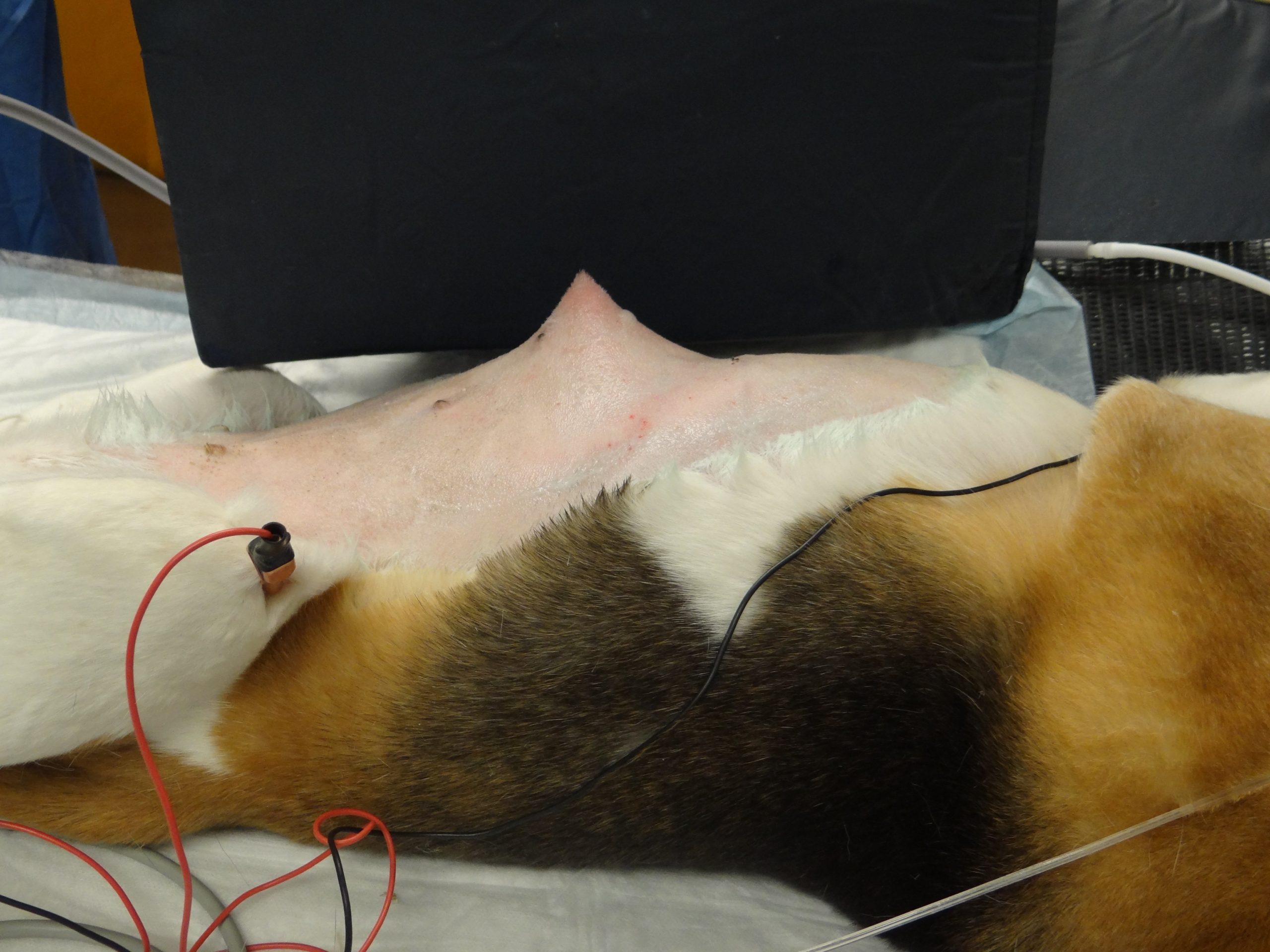

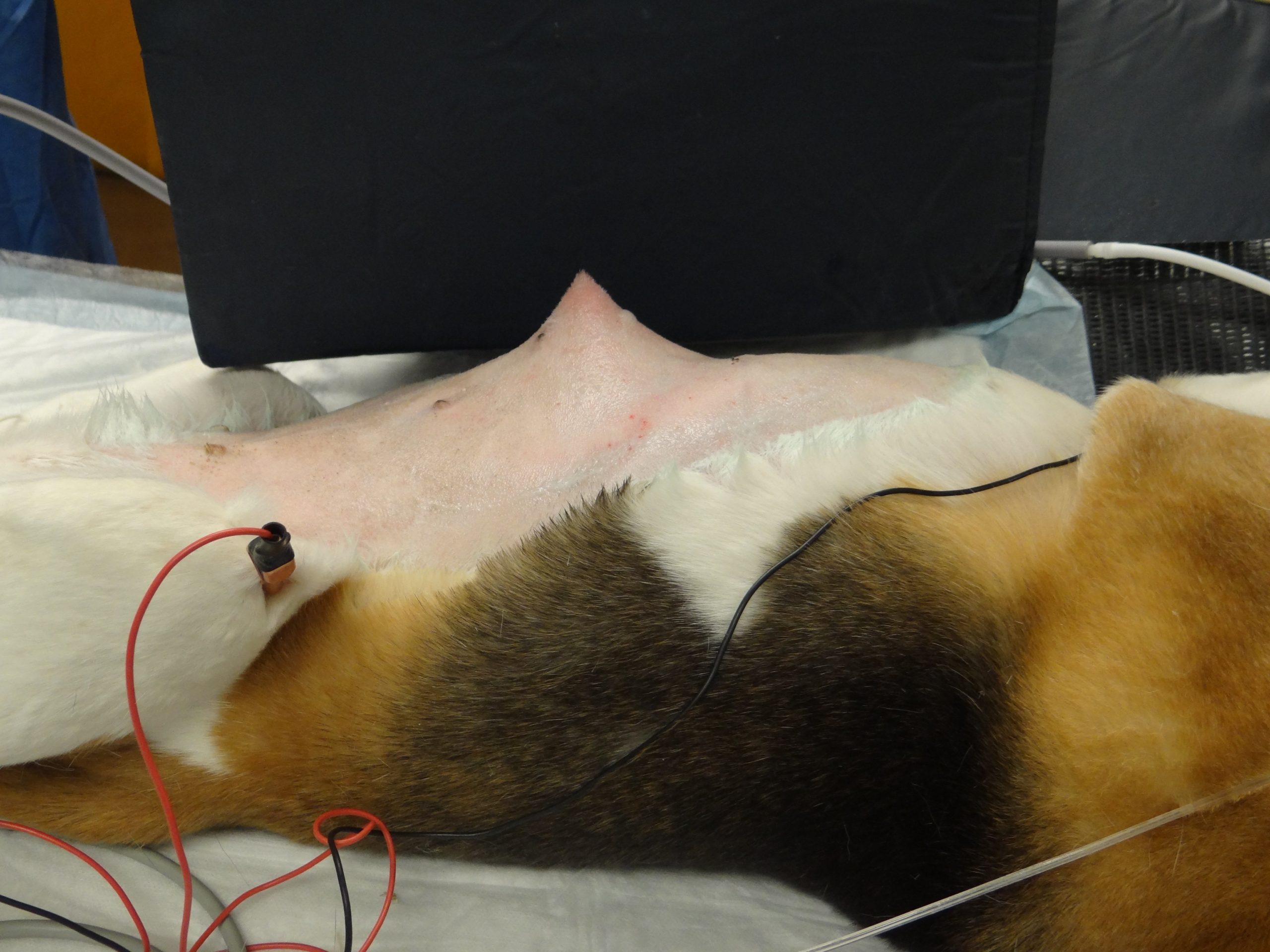

“Many of the objects that can migrate in a dog’s body — like quills, foxtails, and splinters — are made of cellulose. That material is radiolucent, meaning it can’t be seen on an x-ray, which makes finding these objects difficult. The best way to image them is by using ultrasound, but even with that, they are so small that they are easy to miss, although it should be noted that ultrasound can also be good for helping us find these objects during surgery. Kabob sticks are a little easier to see on x-rays than some other objects because they are larger. They are also relatively easy to find in surgery. At Tufts, we tend to perform surgery to remove a dislodged kebob or teriyaki stick on the order of once a year.”

Finding — and removing — other stick-shaped objects

© victoriasky | Bigstock

Foxtails. Found pretty much only in western states like California and Colorado, foxtails are the little barbed seeds of the foxtail plant, a grass-like weed. They can make their way into a dog’s body through its feet, migrating into the skin from between the toes, or from inside the ears, eyes, mouth, or other areas of the body. They can even simply dig into a patch of skin virtually anywhere on the body. And once they’re inside, they start migrating.

The barbs allow them only to move in one direction. They can’t back up. (Think of a car not being able to back up at the rental agency in an airport because of the orientation of the barbs in the road bed just as you check out.) Eventually, the foxtails get stuck somewhere on their forward path. That’s when the trouble starts. The presence of the foreign body causes an infection, and the infection eventually finds its way to the exterior. Specifically, the dog will develop a draining track — also termed a fistula — which is an opening in the skin that chronically drains. It’s about a centimeter wide.

Antibiotics won’t help, because as long as the inciting cause of the infection remains in the body, drugs can’t take care of the problem. The only way to get rid of the continuous drainage is to get rid of the foxtail. Easier said than done.

Although it would seem that a surgeon could simply follow the fistula, “that can be very difficult,” says Dr. Berg, a surgeon. “The fistula can be a foot long, but very narrow, so it may not be easy to track. Sometimes we’ll do a fistulogram — inject a contrast agent into the fistula and take an x-ray. If the contrast agent reaches the foxtail, it’s easier to find and remove.

But occasionally,” he says, “the foxtail is never found. It can be hidden near the spine or in a limb. It’s very frustrating. In those cases, the dog just has to live with it.”

Fortunately, Dr. Berg reports, foxtails don’t tend to make a dog feel too sick because the infection is continually draining rather than building up. But dogs can get sick with fever and sometimes worse symptoms depending on where the foxtail is lodged, which is why at the very least, dogs in whom the foxtail is never found tend to be treated with long-term antibiotics. “I’m glad I practice in the east,” Dr. Berg says. “It’s hard when you can’t get to the bottom of something.”

Porcupine quills. “This is one we see in New England,” Dr. Berg says. “Anytime a dog gets quilled, it’s generally going to be in the face. A dog runs up to a porcupine; the porcupine quills the dog, usually around the mouth. A dog will end up with a beard of quills, each a little over an inch or so.”

It’s painful. “Imagine if someone suddenly jammed a whole bunch of needles into your hand,” Dr. Berg says. Indeed, a dog’s muzzle is as sensitive as our hands. That’s where so much of their sense of feeling is.

All quillings should be treated as emergencies, with the dog being brought to the veterinarian as soon as possible because quills will fairly quickly bury under the skin. And like foxtails, they have a tendency to migrate through the body, causing infections and chronic oozing.

The vet will anesthetize the dog and pull out all the quills he can find, although by the time the pet reaches the doctor’s office, some may already have passed through the skin or lining of the mouth. The vet will search in anything that looks like a quill hole while the dog is under anesthesia, but he may not be successful at retrieving quills that have migrated too far. “We tend to tell owners, “We got all we could find, but there could be others,'” Dr. Berg says.

It could be months before evidence of the quill will turn up. A chronic cough suggests a quill, or quills, lodged in a lung or the chest cavity. Or there can be chronic oozing or an infection somewhere inside the body. (Folks out west, the same is true for foxtails. It could be months before there are signs of one somewhere in the dog’s body. And it might not readily be clear that it’s a foxtail seed causing the symptoms. At least with quills, the owner knows what happened — and when.)

Because of delayed symptoms, Dr. Berg advises owners of dogs struck by porcupines that if a dog’s behavior or demeanor changes even months after the incident, they should bring their pet back to the doctor’s office. “We had one dog who, months after a quilling incident for which he was treated, developed a chronic cough,” he says. “It turned out he had several quills that had migrated to his lungs. We had to take out portions of his lungs over two surgeries in order to get them out.”

Splinters. Dogs don’t actually swallow splinters. It’s that some dogs like to chew sticks into a million pieces. It might seem that a tiny sliver of a splintered stick would easily be digested. But, like a quill, a splinter can penetrate the lining of the dog’s mouth and start migrating in the body from there. Most commonly, a splinter will lodge somewhere in the head or neck. It’s very serious and requires prompt treatment. Why? It’s about abscesses, which are severe pools of infection.

Most often, the abscess occurs in the middle of the underside of the neck, right below the dog’s head. This is termed a cervical abscess. It comes from bacteria on the unclean splinter in addition to bacteria from the dog’s mouth that never should have made it to the neck. A dog can fall sick with fever — and a pretty obvious, firm swelling in the area as a result of all the pus and fluid resulting from the infection. In some cases, a dog will even stop wanting to eat and become inactive.

The fix is a surgical incision — not to remove the splinter, which has almost always dissolved by the time the vet finally sees the dog. It’s to let out the pus and give the doctor a chance to flush the area with sterile fluid. The surgeon will also insert a suction drain that remains in place for a couple of days to draw out any leftover fluid. The vet takes a culture of the pus, too, so the correct antibiotic can be prescribed.

When a splinter from a chewed stick lodges behind the eye, it can cause what’s known as a retrobulbar abscess. You might see the dog’s eye protrude, or the eye might simply look red and irritated. Same symptoms as with a cervical abscess: potential fever, loss of appetite, loss of energy and, in this case, a lot of pain around the eyeball.

Treatment for an infection behind the eye sometimes starts with just antibiotics, but if that alone doesn’t work, an incision has to be made, just as for a cervical abscess, to let out the pus. The incision is usually inside the mouth, behind the last upper molar, which is right below the eye.

Sewing needles. “For some reason dogs — and cats — will sometimes swallow sewing needles,” Dr. Berg says. “Often needles and thread together.” For cats that makes sense because they like to play with string-like objects. With dogs, who’s to say? Sometimes they’re just too curious for their own good.

Whatever the reason, the needle will make it down into the stomach and pierce the stomach wall. Or it will get past the stomach into the intestinal tract and pierce the intestinal wall. In rare cases, it will make it all the way through and then out of the body. But more often, wherever a needle lands, it causes an infection, and sometimes, pain.

Unlike kebob sticks, porcupine quills, or most of the other stick-like objects discussed in this article, needles can be seen easily on x-rays. Because they are made of metal, they’re not radiolucent like wood or quills and do not need a contrast agent — or an ultrasound — to be detected. Thus, they’re often not terribly hard to find.

“I once had a dog who had a needle stuck above his soft palate,” Dr. Berg says. “Another dog had one, literally, in his heart — at surgery, a tiny little end of a needle was sticking up out of the heart tissue itself. We grabbed it and pulled it out, and the dog was fine. If it had gone in another couple of millimeters, the result could have been disastrous.

“Generally,” Dr. Berg says, “if we can find a migrating foreign body and remove it, the prognosis is really good. Once in a while, though, a small, radiolucent object becomes stuck somewhere and we simply cannot find it, even with intraoperative ultrasound. In those cases, it becomes the proverbial needle in a haystack, which can be very frustrating, both for owners and us.”