Tufts Animal Behavior Clinic Head Stephanie Borns-Weil, DVM, has always had two dogs in her home since she was 13 years old. Throughout her life she has seen these dogs provide companionship for each other and grieve when their close friend passes on, yet later develop a good relationship with their next “sibling.”

“Having a companion for your dog is really important,” Dr. Borns-Weil says. She understands that not everyone can have or even wants the responsibility of caring for two dogs and comments that deciding to have an “only” dog is a perfectly reasonable way to go. She is glad to see anyone provide a dog a good life in which he is loved by his human family. But she points out that because dogs are innately social animals, there’s no denying that they do benefit from having at least one friend of the same species in their home. After all, you can toss a ball for your dog and wrestle a squeaky toy from his mouth, but you play like a person. Imagine always having to do your favorite activities with an animal who doesn’t quite get it.

Another benefit of a dog having a canine housemate: less stress for the dogs about being boarded when you leave town.

The pairing usually goes well. Dr. Borns-Weil’s dogs over the years have certainly gotten along swimmingly — with the exception of her latest set. In the canine equivalent of speed dating, she took the dog already in her home to local shelters and brought home the shelter animal her dog seemed to like most. Still, the two got off to a rocky start that took a while to get past. “As it turns out, just like people, dogs don’t always know what’s good for them,” she says. She had to work at their relationship in order to maintain peace.

Many of the problems between two dogs in the same house, Dr. Borns-Weil says, come down to plain old sibling rivalry, just as for human children. Each wants first dibs on what matters to him — generally, the familiar stuff like toys, treats, and attention. It’s our job as the ones who are supposed to facilitate good relationships in the household to see to it that each dog feels his needs are met — just not to the exclusion of the other dog’s. But how?

When introducing the second dog to the household:

It might seem that the easiest way to help two dogs in your home get along is to adopt both of them at the same time. That way, it stands to reason, nobody was there first, so nobody will feel he has turf to defend or turf to infiltrate. The two will perceive their claim on their home environment, and their claim on you, equally.

You might also assume it’s a plus if the two dogs are similar in age. An eight-year-old simply is not going to have the same interests or be in the same frame of mind as a puppy — or have the same energy level. But, counterintuitive though it may be, getting two dogs of the same age and at the same time does not decrease the risk of squabbling.

On the upside, differences between two dogs in a household, no matter what their ages and no matter when they arrived, are rarely irreconcilable. That said, the adjustment can sometimes be made more difficult if a puppy is brought into a home where an older dog has already been living. The older dog might tend to be indulgent up front, but perhaps more cranky later on about the younger dog trying to vie for equal status.

“When you bring a puppy into the house, the older dog is usually very tolerant of the younger dog’s antics,” says Dr. Borns-Weil. “You see this even in wolves, where the alpha wolf rolls around like an idiot with a puppy, even letting him bite his face, but he would never allow this with an adult wolf, and it’s the same with dogs.” What it means is that when a puppy reaches social maturity at the age of a year to a year and a half, real jockeying begins. That’s because you now have two adult dogs who believe they have equal standing precisely because the older dog gave in to the pup in so many ways. Fortunately, the dogs almost always work it out, sometimes in ways so subtle you won’t even notice the negotiating.

Of course, you might want to ease the transition by identifying a second dog who enjoys the same pastimes as the dog you already have. For instance, if your dog loves the water, maybe you’ll want a pet with some Newfoundland in him, or some Portuguese water dog, both of whom are genetically encoded to enjoy a good splash-about.

You’ll also want their first meet-up to be on neutral territory — not at your home, which the dog already there feels is his. Initial introductions at home could bring out territoriality that can get the two off on the wrong foot. Instead, try a park, with lots of treats handed out equally to both and lots of praise for happy cavorting. Spend some time with them outside both on and off-leash to ease their sense of comfort with each other in terms of being in close proximity.

When the second dog comes home, perhaps after two or three meetings away from the house, continue fussing over the two of them as they play together but — and this is a big “but” — make sure your original dog gets his food and treats first. He must remain top dog. Don’t worry that it’s not fair to the other. Dogs accept that hierarchy and even expect it. Mixing it up will only derail their sense of the natural order of things.

You also don’t want to pay an inordinate amount of attention to the new dog — at least not in the first dog’s presence. Yes, of course your new pet must get some extra attention, if only to show him the ropes of the household, to show him how things go in your home. But if you coo over the new dog as if the first one isn’t there, he will of course become jealous and possibly resentful. And the new dog may get the message that he is more important — which he is not.

Don’t Intervene in Every Scuffle

As your two dogs settle in together, you may very well see them start to “argue” over resources — a favored couch cushion or a special toy or perhaps your attention. That’s okay. It’s doggie nature, just as it is human nature. Everybody wants the “good” stuff.

You don’t have to worry that either dog is trying to assert dominance. Dominance is an outdated term when it comes to understanding canine behavior, Dr. Borns-Weil says. Neither dog is trying to lord it over the other. In fact, the doctor comments, generally speaking, dogs are not interested in fighting. Even though most have been neutered or spayed, they maintain an instinct that tells them fighting will lessen their chances of passing down offspring. It’s an important point because “the concept of dominance has been misunderstood and misused to the detriment of dogs,” Dr. Borns-Weil says. “It’s used as a justification for very inappropriate, forceful ways of training” in the mistaken belief that a dog needs to be taken down a peg when that’s not the case at all. “I don’t even like to use the D word for that reason,” Dr. Borns-Weil notes.

So what’s the “arguing” about, if not about dominance? It‘s simply about who has prority access to which special items. One dog may really want that seat by the window, while the other may really want to be the first one to get handed a treat or petted. That is, who’s “dominant” is all relative, depending on the situation. It’s not a static thing, and a dog is not thinking, “I’m dominant” but rather, “This really matters to me.”

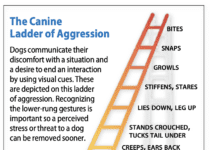

Dogs make their strong preferences clear with behavioral displays that can look concerning but aren’t. “They’ll hold a stance or give a look or a little rumble,” Dr. Borns-Weil says. It very rarely will escalate, so don’t try to play power broker. Let the dogs work it out for themselves. You may not even need to step in with the occasional growling, snarling, air-snapping, or noisy scuffle that subsides on its own with no one getting hurt or frightened. In fact, your doing so can sometimes backfire if you mistakenly reprimand the dog that should have the preferred item.

Consider that if you see one dog giving the other dog a piece of his mind, he may be responding to a provocation rather than starting one, and if you put him “in his place” you will have undermined his credibility in defending himself. You are, in effect, punishing him for protecting something that he has a right to protect, which will prove confusing. Likewise, you could inadvertently end up rewarding the other dog for being pushy. They’ll work it out. Remember, Dr. Borns-Weil says, if one dog is staring while another eats, and the dog being stared at growls, it is appropriate in dog signaling because the dog being stared at is asserting his right to eat his own food without being made uncomfortable.

When to Step In During a Dog Fight

Sometimes things don’t work out according to the normal bell curve, and you do need to intercede. The issue can be excess fear in one of the dogs that leads to undue aggression, a predatory instinct on overdrive, or even exaggerated anxiety.

One time, says Dr. Borns Weil, “a client came in with these two ginormous female pit bulls who had serious fighting between them. He invested a large amount of time and effort to get both dogs under voice control and a lot of environmental management like removing toys the two dogs fought over and supporting the older dog, who had been in the house longer, with first dibs. He also put the newer dog — the one picking the fights — on an SSRI like fluoxetine (Prozac).” The owner eventually had both dogs on SSRIs because both had significant anxiety, one with aggression born of fear.

By degrees, the client was able to shift the dogs’ relationship from sometimes dangerous fighting to a situation that made their world predictable and consistent and without troubling anxiety, thanks to fair management of their resources and use of appropriate medication. “They are doing amazingly well now because the owner was outstanding and exceptional,” says Dr. Borns Weil.

Some of the lessons that owner applied should be applied to all dogs who live in the same home, and even to all dogs, period. He gave them lots of attention and made sure they engaged in lots of physical activity, keeping both their minds and their bodies busy. Dogs need that. The more their needs for exercise and for using their minds are met, the more ratcheted down any unfortunate tendencies will be. Dr. Borns-Weil can’t emphasize enough the importance of “plenty of exercise and mental stimulation” for taking the edge off. She also advises that for dogs who fight severely, “sometimes they have to live on lockdown, in different parts of the house, and then brought together by degrees in a very controlled fashion.”

Unfortunately, once in a great while there is a case where all the proper “parenting” in the world isn’t enough, and one of the two dogs has to be removed from the home. This tends to happen when one of the dogs has a strong tendency toward misplaced predatory aggression. You pretty much can’t train a dog out of that. He is born locked and loaded to chase, catch, and sometimes, kill.

“If a big predatory dog picks up a small dog and shakes it even once,” Dr. Borns-Weil says, you should probably re-home one of the dogs. The bigger dog is not angry or nasty. He’s just acting according to his genetic wiring, and that’s much more serious than two dogs “barking in each other’s faces many times a day,” the doctor says. “One of my patients a while ago killed another dog who was running by,” she adds. “This kind of predatory behavior is very difficult.”

However, Dr. Borns-Weil says, even serious sibling rivalry between dogs can just about always be worked through with patience and understanding. “Dogs have relationships with each other, they are social animals, and it is the exception that they don’t do better in pairs.”