© otsphoto | Bigstock

You know how some people are able to get their dogs to lie down and roll over after they say, “Bang, bang?” Or how some dogs are able to retrieve an item from another room, or even from another floor of the house, and bring it over to the person asking for it? How do people get their dogs to do things like that, which require more steps than just “Sit,” or “Down?”

Tricks that take more than one move are called complex behaviors, explains the head of the Tufts Animal Behavior Clinic, Stephanie Borns-Weil, DVM, and they are taught through shaping. What is shaping? It’s leading a dog through gradual approximations of a behavior until you get her to engage in the very behavior you have in mind. It takes a good deal of patience, but the outcomes can be very rewarding — not just for you, who will enjoy watching your dog perform complicated tasks, but also for your dog, who has an active mind and wants to engage with you in brain-stimulating activities.

Start with something relatively simple

Let’s say you want to teach a dog to go to her mat, put all four paws on it, and stay there. There are a couple of ways you can tackle it, Dr. Borns-Weil says, but one way would be to walk across the mat with a bag of treats in your pocket. The dog follows you (for obvious reasons) and as soon as she sets one paw on the mat, you tell her she did a great job and reward her with some of whatever food you’re using.

Once she has that trick down, you no longer reward her for putting one foot on the mat but give her a treat only when she puts two paws there. The dog is thinking (in whatever way dogs think about things), “I don’t know what this is all about, but if I put two paws on this rectangular thing I get a treat, so I’m going to do it again.” But then after a while, there’s no reward for two paws, only four. Voila, the behavior has been shaped and in the process, the dog believes she has shaped your behavior: “If I want a treat, all I have to do is step all the way onto that mat. My owner is so easy to manipulate.” After a while, Dr. Borns-Weil says, you can begin to add a verbal cue: “Go to the mat.” That way, the dog learns that a reward comes only if you cue her to go onto the mat, not simply if she decides to go on her own.

Learning “by accident”

Another way to shape a dog’s behavior is to reward her for doing something you want when she does it by accident, then work up to rewarding her when she does it on purpose. It’s called the capture method because you’re capturing your pet in the moment rather than leading her to it.

© nsergeyn | Bigstock

Perhaps you would like to teach your dog to ring a bell when she wants to go out. You can hang the bell somewhere, perhaps near the door itself, and at some point she will bump into it. The bell rings and voila, you immediately give her a treat and open the door. With repetition, she will learn that you get up and open the door when the bell is jostled. She may then begin to jostle the bell to get you to open the door.

Dr. Borns-Weil teaches her veterinary students how to shape complex behaviors using a technique she learned in Don’t Shoot the Dog, a book by behavioral psychology expert Karen Pryor. She has one of the students step out of the classroom, and then the rest of the students in the room think up a novel activity for the student to learn. They decide, for instance, that the novel activity will be to pick up a marker and draw a smiley face on the whiteboard.

The student is then invited back into the room with absolutely no idea what’s expected and, just like dogs, very little communication through language. She is guided virtually only through positive reinforcement, which is the way a dog would learn.

The person comes into the room and starts walking away from the whiteboard. No reaction. Then she turns around and heads toward it, at which point her fellow students call out, “Good job! Hey, what a great job!” Then she turns way from the board — remember, she has no idea what’s expected of her, just like a dog doesn’t when you first try to teach a trick or behavior — and everybody stops rewarding by ceasing to call out enthusiastically. Then the student, feeling she is “getting colder,” turns back toward the board again and sure enough, everybody starts cheering her on. She happens to follow up by actually touching the board, and the praise ramps up even more enthusiastically. She runs her hand along the board — more quiet; the behavior has to be shaped just so — and then picks up a marker, at which point the praise once again erupts.

The student writes, perhaps a phrase or a sentence. Quiet. Then she starts making shapes — a triangle, a circle. More praise, until she finally gets to the point that she draws the smiley face inside the circle, which may come after another triangle, and perhaps a square or rectangle. Bingo! The complex behavior has been shaped without punishment, only with patience and the reward of praise as she edged closer and closer, by accident, to the goal.

Teaching your dog a complicated complex behavior

Once you know what it’s like for a dog to learn a complicated series of behaviors without the benefit of a shared language to explain things, it becomes easier to apply the skills necessary to get her to perform what you have in mind.

Maybe you want to teach your pal to roll over and play dead when you say “Bang.” First, says Dr. Borns-Weil, get her to lie down, or just wait till she lies down (capture the first part of the behavior) since dogs naturally lie down all the time. Reward her for that behavior. Then, lure her to roll over on her side by holding a treat over to one side when she’s already down on the floor. Reward her every time she rolls over.

© herreid | Bigstock

After a while, you can cue her to lie down and then immediately roll. From there, once she has that chain of behaviors down pat, start rewarding only when she does the entire chain of lying down and rolling to her side. At that point the cue word “bang” is added and once she learns to do the behavior following the cue, you reward the behavior sequence only after “bang” has been said. (Of course, if she has hip dysplasia or another physical problem that would make doing this uncomfortable, don’t practice this trick with her.) If you want to teach her to learn to roll not to one side but onto her back with her belly up, lure with a belly rub as you are getting started.

To reinforce the behavior, use a clicker

For the best results, click a clicker when the dog does what you want, even when you’re just starting out training her to perform a complex behavior, Dr. Borns-Weil advises. Why? “It’s a secondary reinforcer,” she says. It marks the exact moment that the desired behavior occurs, which is key. Think about getting a dog to roll over just a little bit more than she has been doing as you’re trying to shape a behavior with compound steps. You might call out “Good job,” but by the time you give the dog the food reward, even if it’s just a couple of seconds later, her mind is already somewhere else. She has moved on and will not associate the food with the desired behavior. The clicker, which you use to make a sound at the exact moment that your dog follows through, tells her exactly what she is being rewarded for. She’ll make the connection that the food follows the click, even if it’s a few seconds later.

“It’s like when you get a notice via email that your paycheck has been deposited,” Dr. Borns-Weil says. “You feel paid even though you don’t have your cash in hand yet. It’s predictable. Every time you get the notice, real money follows. The clicker is what they use to teach dolphins to jump through hoops with gradual approximation,” the doctor says. “First they just put the hoop on the water. When the dolphin goes near it, she gets a click and a treat. Once she has that down, then, only when she swims through the hoop does she get a click and reward. Once the dolphin swims readily through the hoop on the surface of the water for a click and treat, the trainer begins elevating the hoop slightly so that the dolphin must jump a little to get through it. When the dolphin does jump to go through it, that now elicits the click and the treat. The hoop is very gradually raised until it is fully above the water line so that the dolphin must leave the water to jump through it. If the dolphin begins to swim under the hoop, it is lowered closer to the water, and a previous level of performance is rewarded until the dolphin is ready to try the next step again. It’s in this way that the behavior gets shaped through a series of steps, and the trick is mastered.

Why a clicker to make the sound? It needs to be a novel noise, not one the dog hears in other contexts, or the association between clicking and getting a treat won’t be made. Praise alone — like “Good dog” — the dog will hear lots of times in other situations, whether or not food follows.

You can choose a novel word that the dog will not hear in other contexts instead of using the clicker, Dr. Borns-Weil says. And you can put a particular emotion into your voice to give it even more meaning for the dog. “Dogs are incredibly perceptive,” she points out. “They have 10,000 years of being bred to pay attention to us.” It’s for that reason that people commonly use the word “yes” said in a special upbeat tone that the dog is unlikely to hear in casual conversation. The dog “gets” it.

Ramping it up

Okay, now it’s time to teach your dog to bring your slippers — from upstairs (as long as she is not afraid of stairs and doesn’t have difficulty climbing them). How do you start?

First, know that this is going to be easier with a dog who has some retriever in her, since retrieving is in her blood. Not all dogs are going to learn all tricks.

Second, don’t begin with your slippers but with a really good toy. Reward your dog for picking up the toy in her mouth. Then reward her when she happens to see it on the staircase, where you’ve placed it, and picks it up. Follow that up by placing it on a higher step and rewarding her only when she retrieves it from that higher step.

After a while (and this could take a couple of weeks), add a verbal cue with an enthusiastically uttered “Go get your toy!” Reward her for doing just that, putting more and more distance between your pet and her toy, until she can reach the point of retrieving it when it’s out of sight in one of the upstairs bedrooms. Once she masters that piece of it, it will be easy enough to teach her to come back to you with the toy in her mouth.

From there you can switch to slippers, perhaps slippers scented with something delectable or into which you have placed some treat. And so on.

There’s no one right sequence of events. Trial and error are definitely part of it. Your starting point may be too difficult, or the toy you’ve chosen may not be motivating enough. If you’re patient with yourself as well as your dog (and why shouldn’t you be — it’s not like there’s a deadline), there’s a good chance the two of you will have success.

If it’s not fun, stop

Many dogs love mastering tricks with behavior-shaping. “It helps them get into learning mode, and they know they’re about to have fun,” Dr. Borns-Weil says. Moreover, she points out, “they get to try all different kinds of things, and in the learning, they get a sense of control and agency.” And they do love shaping our behavior: “Ah, which posture or movement will get her to click and dispense the treat?”

That said, if at any point the dog becomes frustrated, it’s time to back off and do something easier because if it’s not fun, it’s not going to work.

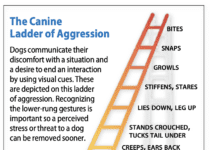

How will you know if your dog is becoming frustrated? “If she starts licking her lips, wandering around and sniffing, or getting water even if she has already satisfied her thirst, you’re being given signs that she is starting to lose focus,” Dr. Borns-Weil says. These can even be signs that she doesn’t want to disappoint you but feels “stuck.”

The thing to do at that point is to cue the dog to perform a trick she already knows very well — like “shake hands” — reward her with hearty praise, and end the session. Then come back and try it again later — “maybe a few times a day in short increments,” Dr. Borns-Weil says.

The pattern of learning is “incredibly variable,” she adds, “depending on a dog’s ability to focus and on her learning capacity.” That is, some dogs are simply going to be better at it than others, and will also enjoy it more.

One thing is certain, says the doctor. Dogs as well as people would rather have their behavior shaped through positive reinforcement than be criticized. It’s advice well worth applying not just when you’re teaching your dog to perform complicated tricks but for interacting with her in general.