Perhaps you have heard of athletes who tore their ACL — the acronym for a ligament in the knee called the anterior cruciate ligament. Olympic skier Lindsey Vonn and NFL quarterback Tom Brady are two examples.

Dogs can suffer the same injury, except in our canine friends the ligament is called the CCL, for cranial cruciate ligament. Dogs also experience the tear differently. When it happens to people, the rupture of the ligament is sudden, occuring from a load that is too great for the ligament’s structure (usually because of a trauma) and causing severe pain. The person often crumples to the ground and is out for the rest of the season, undergoing surgery and rehabilitation.

When it happens to a dog, on the other hand, the rupture occurs gradually, over time. The lameness starts out mild, then progressively worsens as the ligament tears more and more until finally rupturing completely. The reason for the difference is that while people suffer acute overload injuries (think of a rope of a certain strength that can withstand only so much pressure before it breaks), in dogs the disease is a degenerative process. The ligament slowly weakens with time and eventually ruptures during normal daily activities.

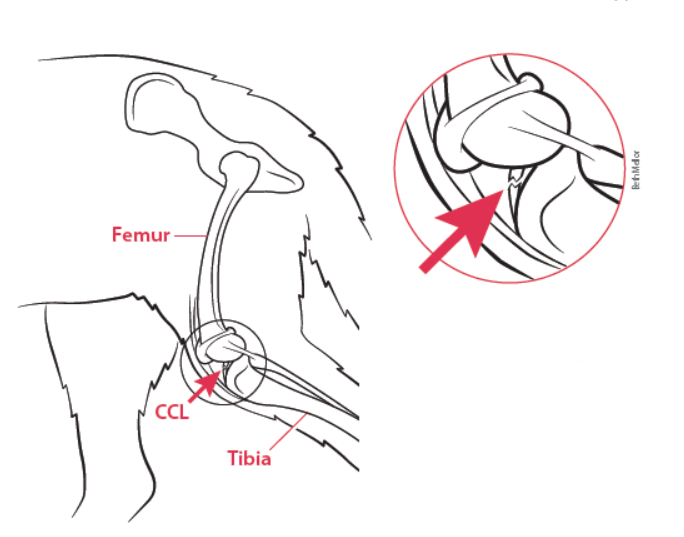

What it means anatomically is that the dog’s knee is no longer stable. When the CCL is intact, it connects a bone above the knee to a bone below the knee and keeps them from sliding too far past each other within the knee joint. The bone above the knee is the thigh bone (femur), and the bone below the knee is the shin bone (tibia).

However, once the CCL is torn and therefore can no longer do its job, the femur slides too far along a slope at the top of the tibia. That sliding happens every time a dog moves around or walks, and it causes debilitating pain.

To help keep your dog from tearing a cranial cruciate ligament in the first place:

- Don’t make him a weekend warrior who sleeps on the couch all week and then overdoes it on Saturdays and Sundays. A mostly sedentary life punctuated with a little bit of very strenuous physical activity is a recipe for ligament tears.

- Keep your pet trim. It’s one of those instances where intuitive sense bears out. The more pressure on ligaments (and joints) via excess poundage, the more likely they are to give way.

Surgical solutions

Anyone who has a dog with a completely ruptured CCL should consider surgery to stabilize the knee joint. It’s true that in dogs weighing less than 30 pounds or so, conservative, non-surgical treatment that includes up to two months of rest and anti-inflammatory medications may take down the pain, along with a weight-loss regimen if the animal is overweight. But the two misaligned bones will continue to rub against each other as they pass and may cause pain and a decreased range of motion down the line in the form of bone spurs and arthritis. Only surgery can stabilize the joint and help mitigate those complications. For larger dogs, conservative approaches won’t have much of an effect even initially. You really need to consider going straight to the surgery.

There are a number of different types of operations that can stabilize the knee following a torn CCL. One of them is called a lateral suture. It effects stabilization with a length of 40- to 100-pound test nylon fishing leader line.

Another is called the tibial plateau leveling osteotomy, or TPLO. Developed by Dr. Barclay Slocum of Eugene, Oregon, and used in veterinary practices throughout the country, it involves a bone plate. Once the tibia is cut and re-angled during the operation, the plate is placed on the tibia to stabilize the area, holding the bone in place until it heals. A specialized bone plate for the TPLO procedure was developed with the help of Tufts surgeons Michael Kowaleski, DVM, and Randy Boudrieau, DVM.

Surgery to repair a ruptured CCL will not automatically prevent the development of arthritis down the line. But it will most certainly slow its progression, keeping a dog more comfortable in his later years. In fact, since such CCL operations are frequently performed on dogs heading from middle age into old age, stalling the development of serious arthritis can often take a dog well into the latter part of his geriatric years — or all the way through his life — without serious arthritis complications.

An operation to stabilize a dog’s knee joint once the CCL has ruptured is not inexpensive, easily running into several thousand dollars (one reason that having health insurance for your pet makes such good sense). But within a few weeks, the dog will enjoy a better quality of life. Granted, a dog who has had his knee joint stabilized may never be able to jump to catch a Frisbee in the way he used to or hit the black diamond slopes come ski season, but he’ll be able to frolic and run after squirrels again just fine.

Does a clicking sound when the limb is extended indicate this kind of injury?